Patient and Provider Perceptions of Opill®

- Original research

Kayla Cao*

Student, Duke University

Candice Holley

Clinical Training & Data Manager, Take Control Initiative

*corresponding author

As the first FDA-approved over-the-counter birth control pill, Opill® is significant in eliminating the need for prescriptions, reducing wait times, and providing easier access to contraception—especially for underserved populations such as adolescents, the uninsured, gender-diverse individuals, and those in contraceptive deserts.

Despite its advantages, awareness and perceptions of Opill® among patients and clinicians remain unclear. This is especially true in Oklahoma, where policies often restrict comprehensive sexual health education and reproductive rights. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate patient and clinician perspectives on Opill® so that it can be more accessible to all.

Two surveys were conducted within Tulsa County: one targeted patients and the other targeted clinicians. Results revealed substantial gaps in awareness and education about Opill®, as well as concerns about its cost. Clinician responses indicated general support for over-the-counter birth control but highlighted worries about adequate patient education on Opill®.

These results highlight the importance of comprehensive sexual health education and supportive policies to enhance Opill®’s accessibility and effectiveness. Given Oklahoma’s current struggles with OB-GYN shortages and restrictive abortion laws, it is vital to create a policy landscape that encourages education and accessibility of options such as Opill®.

Introduction

Opill® is the very first Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved, over-the-counter birth control pill.1United States Food and Drug Administration, “FDA Approves First Nonprescription Daily Oral Contraceptive,” FDA, July 13, 2023. This marks a significant advancement in increasing accessibility, as it provides a contraceptive option that can be obtained without a prescription. Opill® eliminates the long wait periods for a medical appointment, which is on average 31.4 days for an

obstetrician-gynecologist (OB-GYN).2Oliver Kharraz, “Doctor appointment wait times are getting worse,” STAT News, May 2, 2023. Furthermore, since Opill® is widely available at many physical and online entities, it could act as a stop-gap for those who are waiting on a doctor’s appointment for another type of contraceptive method. It also alleviates other potential stressors that may occur on the day of an appointment, such as issues arranging transportation, time off of work, or childcare coverage—all of which could lead to no-show appointments.3Sharon Brandwein, “The top reasons patients no-show or cancel,” Tebra, December 18, 2023. Other populations that can benefit from over-the-counter oral contraceptive pills are adolescents and first-time contraceptive users,4Alana K. Otto et. al., “It’s Time for Over-the-Counter Oral Contraceptive Pills,” Journal of Adolescent Health 72, no. 6 (2023): 829-830. the underinsured and uninsured,5Brittni Frederiksen et. al., “Contraception in the United States: A Closer Look at Experiences, Preferences, and Coverage,” KFF, 2022. gender-diverse individuals,6Celeste Krewson, “Survey finds interest in progestin-only pills among transgender populations,” Contemporary

OB/GYN, June 25, 2024. and those who live in contraceptive deserts—areas that lack access to health centers that offer a full range of contraceptive methods.7Power to Decide, “Access to Birth Control and Contraceptive Deserts,” April 2019.

Although reproductive justice advocates may have circled and highlighted the day Opill® was released in their calendars, it is unclear where others stand on this issue. In Oklahoma, a state where sexual health education is optional, will Opill® be able to reach the populations that it hopes to help? As a state, Oklahoma received a D- grade for its overall state policy on sexual education by SIECUS. Furthermore, there are constant legislative threats to Oklahoma’s sexual health education, such as House Bill 3120 which passed in a committee hearing this legislative session.8Jana Hayes and Alexia Aston, “Oklahoma bill would shift sex education to opt-in, limit teaching HIV/AIDS or contraception,” The Oklahoman, February 25, 2024. Also known as the Parents’ Bill of Rights, this bill would have made sex education opt-in, while also limiting the teaching of contraceptive methods. Oklahoma currently adopts an opt-out policy for sexual education, meaning that a child will automatically receive sex education unless their parent actively chooses to take them out.9Sex Ed for Social Change, “State Profiles: Oklahoma State Profile,” SIECUS, 2022. Changing this requirement to an opt-in policy is problematic because now parents must actively give permission for their child to receive sex education. This creates unnecessary barriers that prevent students from getting the sex education they need. This bill could join a variety of other legislation that has negatively shaped Oklahoma’s sexual education such as Oklahoma Statutes 70-11-103.3 and 70-11-105.1, which require schools to provide human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) prevention education. Under these statutes, AIDS prevention education includes teaching children that “engaging [in] homosexual activity [and] promiscuous sexual activity…. is now known to be primarily responsible for contact with the AIDS virus” and that “avoiding the activities specified [above] is the only method of preventing the spread of the virus.”10Sex Education Collaborative, “Oklahoma: State Sex Education Policies and Requirements at a Glance,” accessed November 17, 2024. Due to the incomplete, and often inaccurate, nature of Oklahoma’s sexual education, it becomes pertinent to investigate what Oklahomans know about Opill® or if they even know it exists.

Beyond the landscape of sexual education, Oklahoma’s abortion policies present an equally complex and restrictive terrain. In 1973, a Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade established the right to have an abortion in the United States.11“Roe v. Wade,” Oyez, Accessed November 18, 2024. In June 2022, the case was overturned, indicating that there is no longer a federal constitutional right to abortion.12Nina Totenberg and Sarah McCammon, “Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade, ending right to abortion upheld for decades,” NPR, June 22, 2024. On that same day, Oklahoma reinstated its pre-Roe abortion policy through a trigger law, which now “criminalizes all abortions except when ‘necessary to preserve’ the life of the pregnant person.”13“Oklahoma,” Center for Reproductive Rights, Accessed November 18, 2024. This setback affects patients and healthcare providers alike. One daunting trend that has taken hold in states with restrictive abortion policies such as Oklahoma, is the mass exodus of OB-GYN providers. Highly skilled doctors, specializing in handling complex and risky pregnancies are leaving their practices, with 75% of OB-GYNs responding to a survey saying that “they were either planning to leave [Oklahoma], considering leaving or would leave if they could.”14Sheryl G. Stolberg, “As Abortion Laws Drive Obstetricians From Red States, Maternity Care Suffers,” The New York Times, September 7, 2023. Understanding perceptions of Opill® is clearly crucial in this restrictive landscape, as increased access to contraception may represent one of the few remaining avenues for reproductive autonomy.

When viewing Opill® through the lens of a clinician, it can also get foggy. Although the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) supports Opill®, providers also cite concerns about losing patients and changing the patient-provider relationship.15American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Gynecologic Practice, “Over-the-Counter Access to Hormonal Contraception,” ACOG, October 2019. Even though Opill® does not require a prescription, providers and health centers can act as valuable partners and credible information hubs for Opill®. Therefore, an investigation into provider perceptions of Opill® is also needed to better understand what role clinics can play in this new era.

As a whole, there is a scarcity of data that indicates where the general public and clinicians stand regarding Opill®. Through the literature review, only one article was found that surveyed women’s “reactions” to Opill®,16Alisha H. Gupta, “Women React to News About an Over-the-Counter Birth Control Pill,” The New York Times, July 14, 2023. and no articles or studies were found that investigated provider perceptions of Opill®. It is vital to collect this information so that Opill® can increase its reach to everyone and use providers as advocates for this option.

Methodology

In order to provide a better understanding of where patients and clinicians stand on this new birth control option, two surveys were disseminated within Tulsa County. A total of 168 responses were collected.

The first survey targeted patients—non-clinicians not in the reproductive health space—who currently or previously lived in Tulsa County. The patient survey contained 14 questions, with 12 questions requiring an answer (Appendix A). A Spanish translation of this survey was also made available to survey respondents (Appendix B). To ensure a wide range of respondents, multiple forms of advertisement and dissemination were used. The survey was advertised on various social media sites and other communication platforms. Flyers were also disseminated at local community events that welcomed all ages and demographics (Appendix C). Additionally, monetary incentives in the form of gift cards were offered to the first 70 respondents to attract respondents and thank them for their time. By the end of the survey timeline, 84 responses were collected (Appendix D).

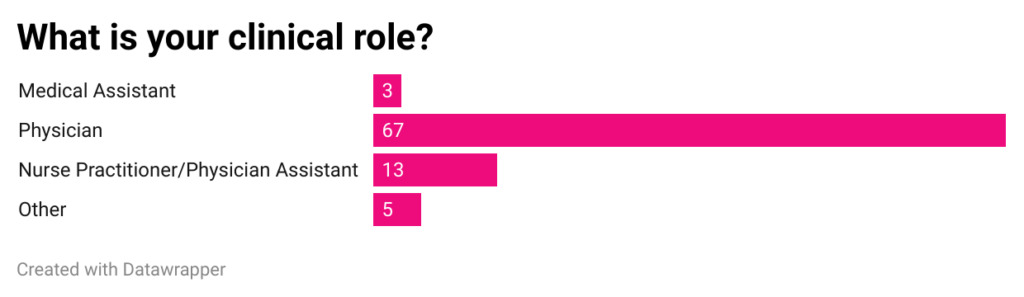

The second survey targeted clinicians in the reproductive health space, practicing in Tulsa County. The term “clinicians” was used to broadly encompass those who work in a clinical setting; however, the majority of respondents were physicians (Figure 1). The clinician survey contained 6 questions, with 5 questions requiring an answer (Appendix E). This survey was disseminated by contacting individual providers, advertising it in reproductive health newsletters, and including it in presentations to local providers. No incentive was offered to these respondents. By the end of the survey timeline, 84 responses were collected (Appendix F).

Figure 1: Bar graph of the responses to the first question of clinician survey.

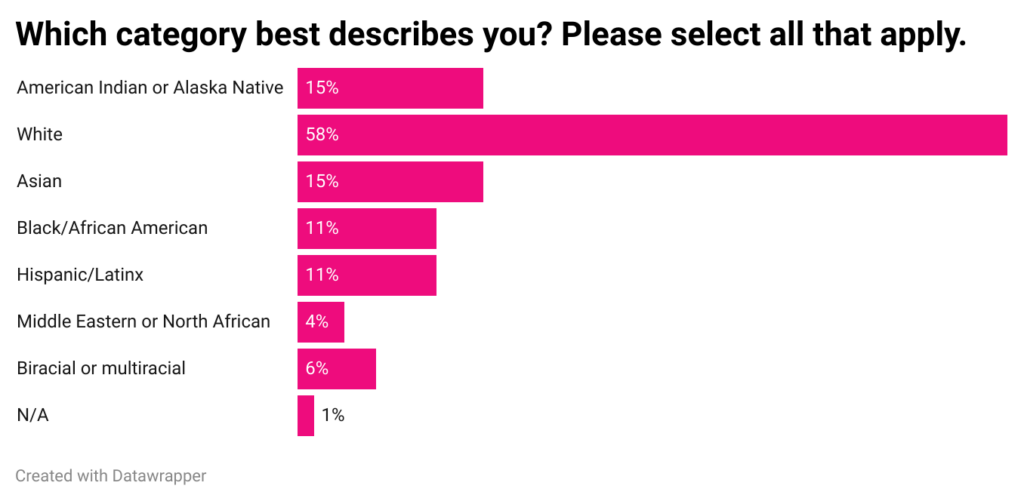

One limitation of this study design is that the demographics of respondents were not as representative as desired. 58% of respondents in the patient survey identified as White (Figure 2). Although this question was optional, 95% of respondents answered the question; therefore, it is fairly representative of the demographics of the respondents. There is no doubt that this demographic is highly informative. 99% of all reproductive-age women in the United States will use some form of contraception in their lifetime,17Kimberly Daniels and William D. Mosher, “Contraceptive methods women have ever used: United States,

1982-2010,” National Health Statistics Reports 62 (2013): 1-15. meaning that this study is pertinent to any prospective or current contraceptive user. Furthermore, the amount of White respondents also corresponds to the amount of Tulsa County residents who are White (63%).18United States Census Bureau, “QuickFacts: Tulsa County, Oklahoma,” United States Census Bureau, accessed November 17, 2024. However, a larger minority representation is also valuable, as all adverse family planning outcomes are more likely to occur among minority women.19Christine Dehlendorf et al., “Disparities in family planning,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 202 no. 3 (2010): 214-220. Furthermore, minority women are less likely to use contraception and have higher rates of contraceptive failure compared to White women.20Dehlendorf et al., “Disparities,” 214-220.

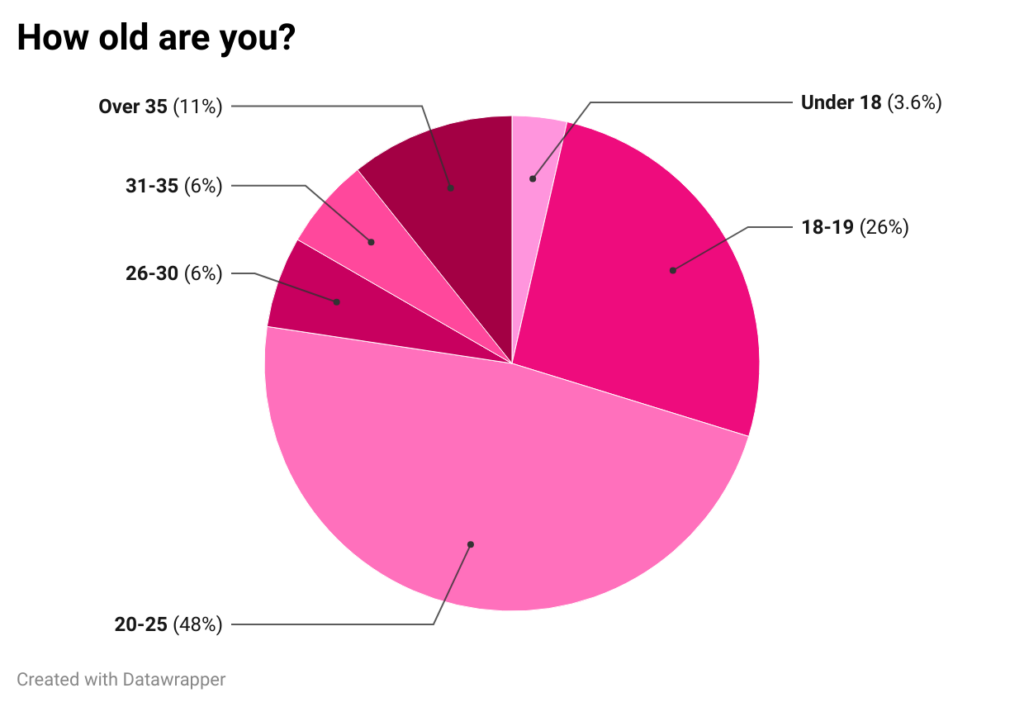

Additionally, 77.6% of patient survey respondents were under the age of 25 (Figure 3). A larger representation of this demographic is helpful in that oral contraceptive use generally decreases in age, with 19.5% of women aged 15–19 and 21.6% of women aged 20–29 currently using the pill, whereas only 10.9% of those aged 30–39 and 6.5% of women aged 40–49 are. Furthermore, for women who are aged 20 and older, female sterilization increases with increasing age. However, obtaining more representation for older participants would have been ideal, as current contraceptive use increases with age: 38.7% of women aged 15-19 use contraceptives whereas 74.8% of women aged 40-49 use contraceptives.21Kimberly Daniels and Joyce C. Abma, “Current contraceptive status among women aged 15–49: United States, 2017–2019,” National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief no 388 (2020). Although Opill® is an oral contraceptive and is therefore less likely to be used by older contraceptive users, it is important to gather data on an older demographic; especially since birth control like Opill® is the first of its kind. This ensures that conclusions are based on evidence rather than assumptions, as novel interventions may yield unexpected patterns of use or effectiveness across different populations.

Figure 2: Bar graph of the responses to the fourth question of patient survey. This question was optional.

Figure 3: Pie chart of the responses to the eighth question of patient survey.

Discussion

Based on the results of the patient survey responses, three themes emerged: lack of awareness, level of skepticism, and cost barriers. Clinician survey responses indicated general support for Opill® and over-the-counter birth control in general.

Lack of Awareness

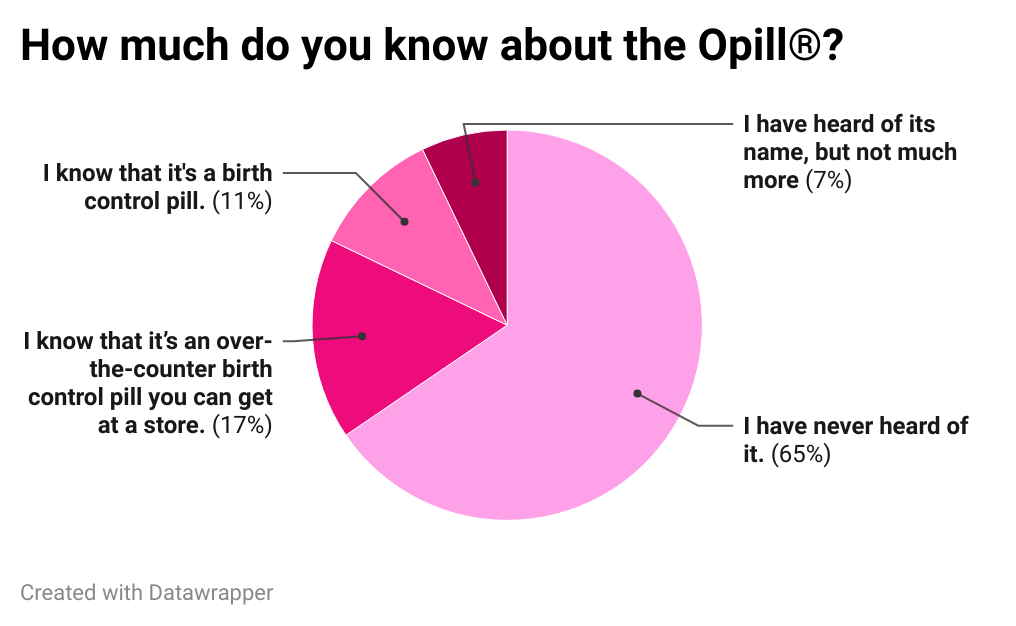

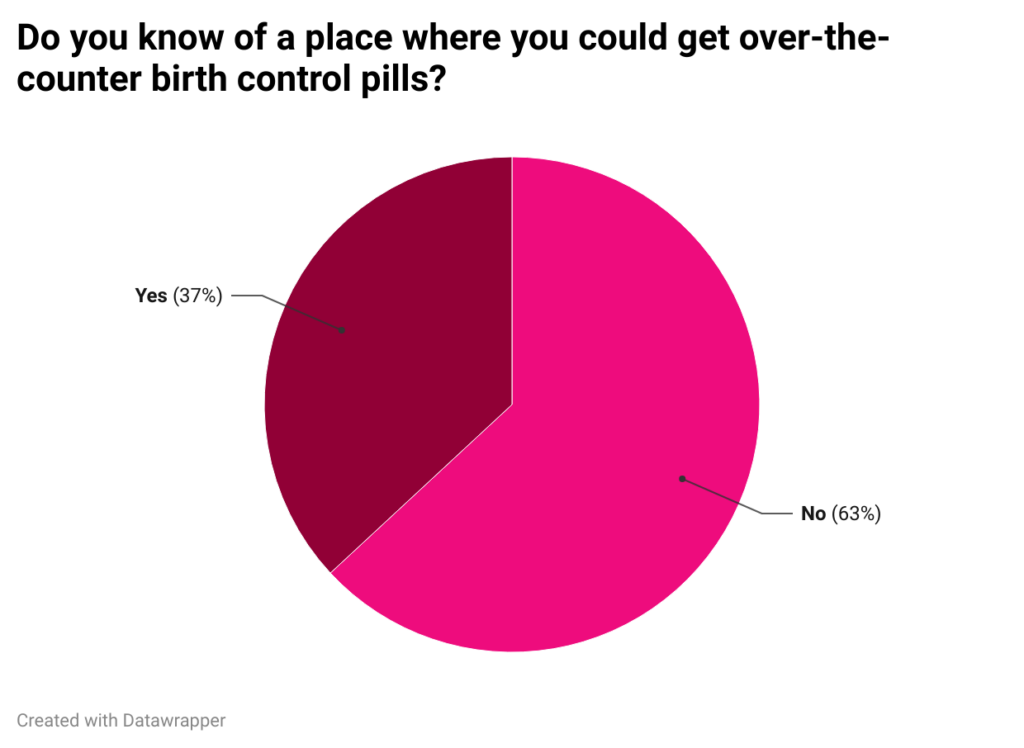

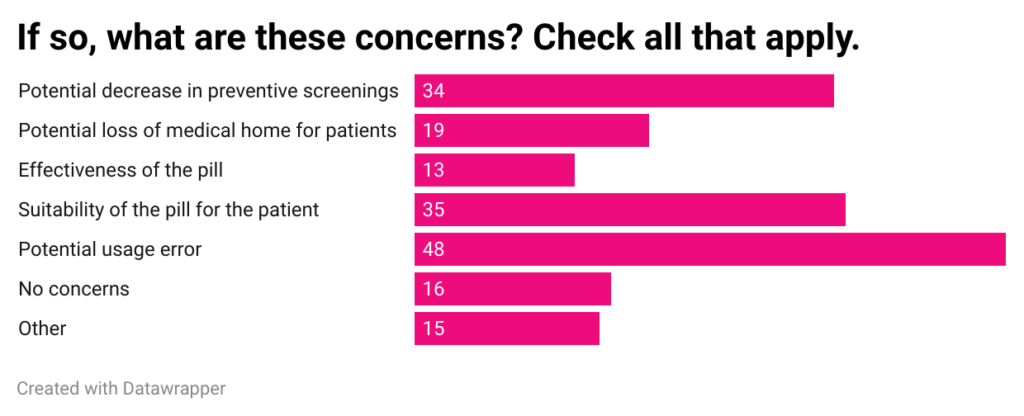

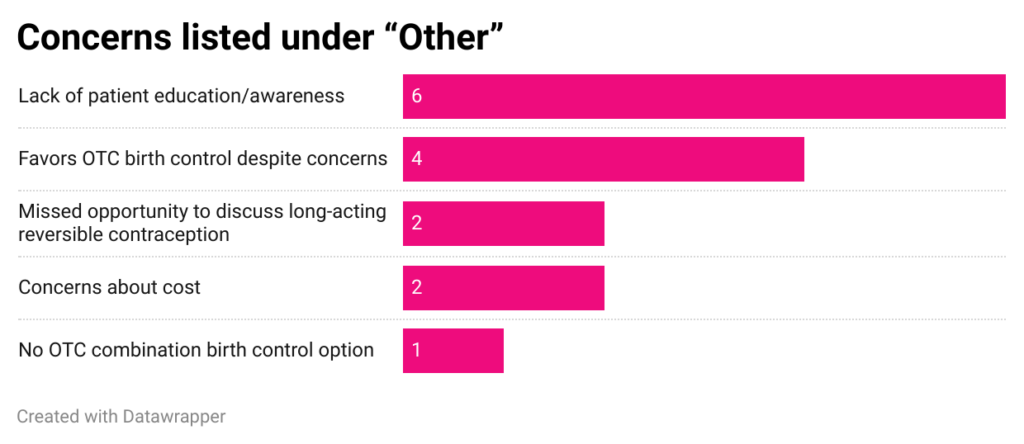

Opill®’s biggest advantage is its wide availability due to its status as an over-the-counter medicine. However, this benefit becomes futile if no one knows about it. As Figure 4 indicates, 65% of respondents had never heard of Opill®. Furthermore, Figure 5 shows that 63% of respondents did not know where they could find over-the-counter birth control pills. Clinicians are also concerned about patient education and awareness, with the most cited concern being “potential usage error” (Figure 6). Also, when asked to list any additional concerns they may have, four providers cited more specific concerns about patient education about Opill® such as knowledge about possible side effects (Figure 7).

The consequences of not knowing about this widely available and accessible form of birth control can range far and wide in a state that has restrictive abortion bans and OB-GYN shortages. The Guttmacher Institute’s interactive abortion policy map put Oklahoma’s abortion policies under the category of “most restrictive.” Oklahoma was already experiencing severe OB-GYN shortages pre-Roe.22Eriech Tapia, “Oklahoma faces shortage of OB-GYNs,” The Oklahoman, August 27, 2017. Post-Roe, this issue will only be exacerbated as states with restrictive abortion bans like Oklahoma risk losing a generation of OB-GYN physicians.23Maryn McKenna, “States With Abortion Bans Are Losing a Generation of Ob-Gyns,” WIRED, June 20, 2023. Given the current reality of Oklahoma’s reproductive care, it becomes vital that birth control methods like Opill® are known and accessible.

Figure 4: Pie chart of the responses to the first question of patient survey.

Figure 5: Pie chart of the responses to the twelfth question of patient survey.

Figure 6: Bar graph of the responses to the third question of clinician survey.

Figure 7: Bar graph of the responses that were written under “Other” to the third question of clinician survey.

Level of Skepticism

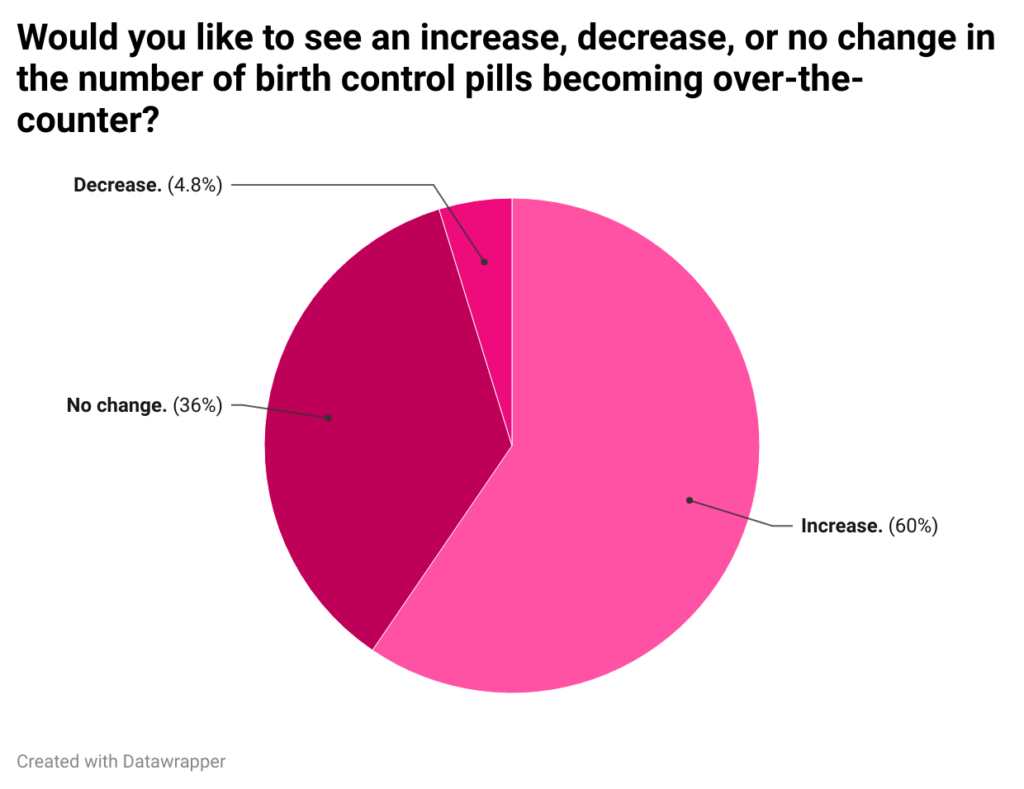

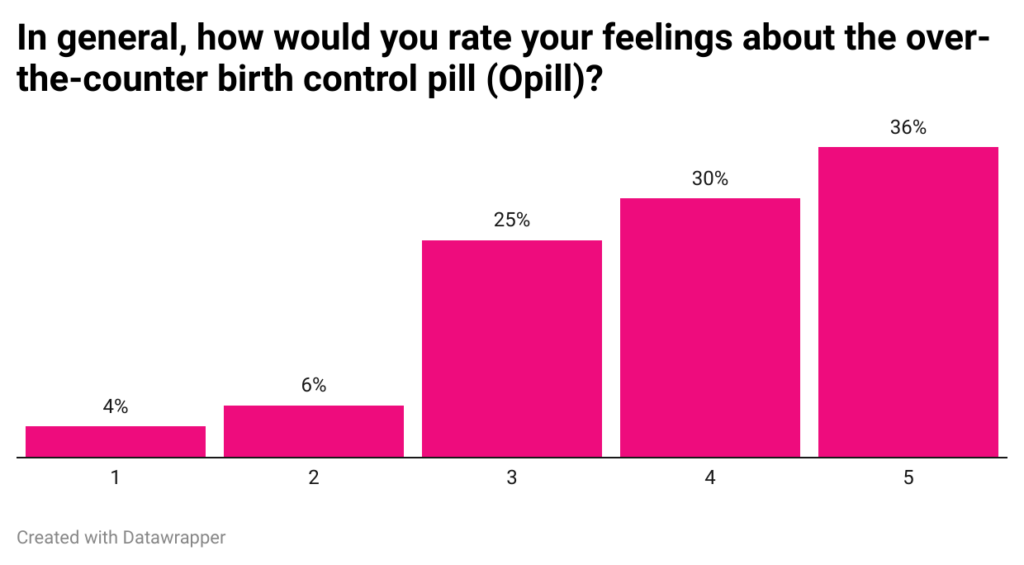

Birth control pills either contain (1) both estrogen and progestin or (2) only progestin. Opill® is a progestin-only pill (POP). POPs have been available to the public since 1973,24Donna Shoupe, “The Progestin Revolution: progestins are arising as the dominant players in the tight interlink between contraceptives and bleeding control,” Contraception and Reproductive Medicine 6, no. 3 (2021). and have been said to be safer than Tylenol.25Melissa Hartman, “Opill: The First Over-the-Counter Daily Oral Contraceptive,” John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, July 13, 2023. Furthermore, FDA requirements for over-the-counter medicines are thorough. In order to gain approval for a product intended for nonprescription use, Opill® had to prove that it was safe and effective for consumers to use independently without needing help from a healthcare provider.28 Additionally, Figure 6 indicates that the effectiveness of the pill was the least popular concern among providers. In fact, 60% of the providers indicated that they wanted to see an increase in the number of over-the-counter birth control pills in the future (Figure 8). Furthermore, the majority of providers had positive feelings about Opill® according to clinician survey results (Figure 9).

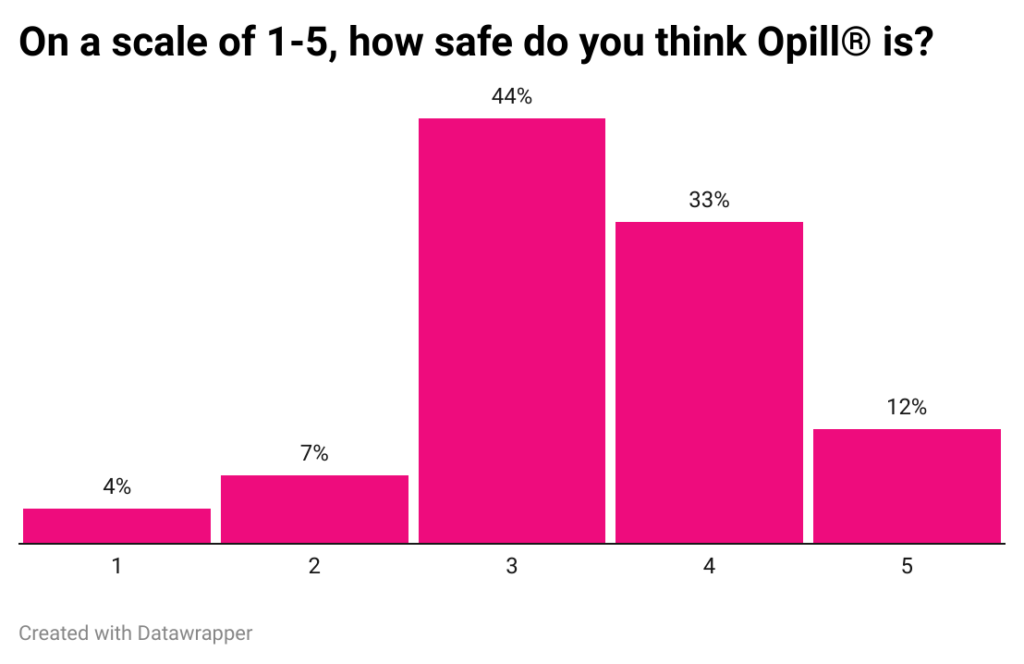

However, public opinion does not reflect Opill®’s safety and efficacy record among trusted institutions and providers alike, as 44% of patient survey respondents indicated neutrality when asked about how safe they thought Opill® was (Figure 10). This is concerning given that a lack of accurate knowledge about contraception can “limit efforts to obtain contraception and continue using it.”26Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Unintended Pregnancy, The Best Intentions: Unintended Pregnancy and the Well-Being of Children and Families, (National Academies Press (US), 1995), ch. 5. The issue of contraceptive misinformation is especially prevalent today, as there has been a recent explosion in misinformation on social media.27Lauren Weber and Sabrina Malhi, “Women are getting off birth control amid misinformation explosion,” The Washington Post, March 21, 2024. Medical professionals report an emerging pattern: more patients arriving with birth control concerns shaped by social media personalities and commentators; however the magnitude of this phenomenon currently remains unknown.28Weber, “Women.” This disconnect between clinical evidence and public perception underscores the urgent need to strengthen patient education about Opill®.

Figure 8: Pie chart of the responses to the fourth question of clinician survey.

Figure 9: Bar graph of the responses to the fifth question of clinician survey.

Figure 10: Bar graph of the responses to the third question of patient survey. “1” indicates “extremely unsafe” and “5” indicates “extremely safe.”

Cost Barriers

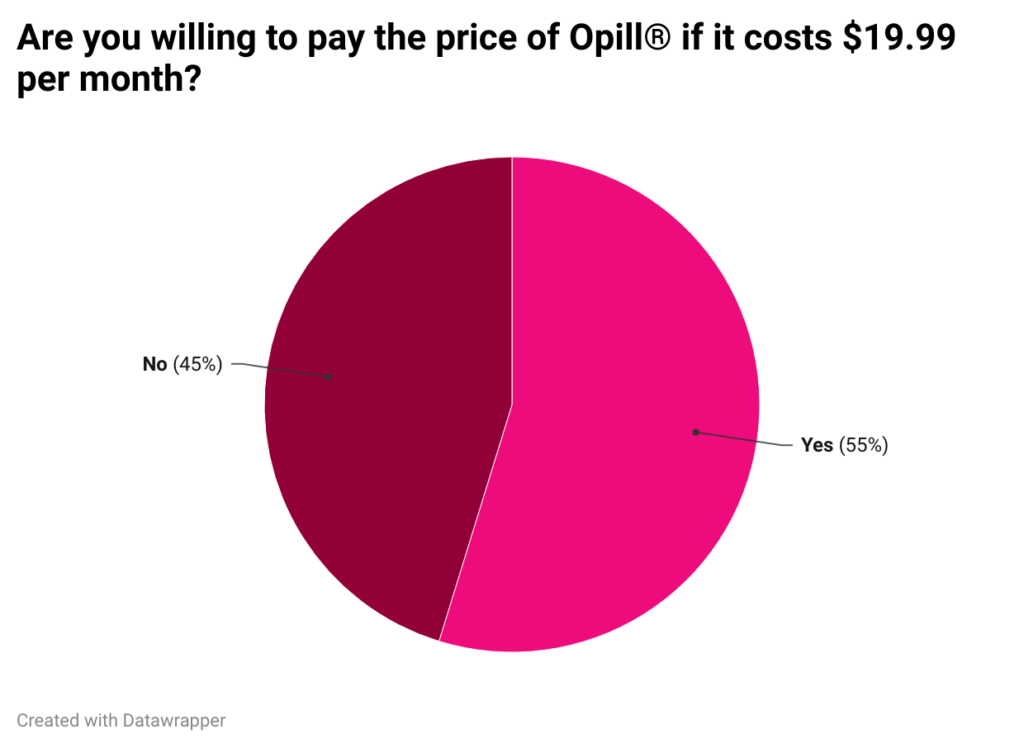

Opill® became available for sale in March of 2024, with a retail price of $19.99.29Sydney Lupkin, “First over-the-counter birth control pill now for sale online,” NPR, March 18, 2024. But as the CEO of Power to Decide, Dr. Raegan McDonald-Mosley correctly declares, “True access means it’s available over-the-counter and affordable for all.” According to the patient survey results, there is a split in opinion on whether or not they would be willing to pay the retail price of Opill®, with a narrow majority of 55% indicating that they would (Figure 11). Clinicians also expressed concerns about Opill®’s pricing when asked about any additional concerns they had (Figure 7). Cost barriers are still a fundamental issue of contraception. In a study across three

states—Arizona, Iowa, and Wisconsin—nearly 20% of study participants reported experiencing financial and insurance-related barriers that hindered their access to their preferred birth control method.30Liza Fuentes, et al., “Primary and reproductive healthcare access and use among reproductive aged women and female family planning patients in 3 states,” PLOS ONE 18, no. 5 (2023). Furthermore, in a qualitative study focused in the Boston area, contraceptive users described costs as a “deterrent” and is what often caused them to stop using contraceptives altogether.31Amanda Dennis and Daniel Grossman, “Barriers to contraception and interest in over-the-counter access among low-income women: A qualitative study,” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 44, no. 2 (2012): 84-91. Therefore, it is essential to ensure that Opill® is affordable for all in order to fulfill its potential as a widely accessible over-the-counter contraceptive option.

Figure 11: Pie chart of the responses to the eleventh question of patient survey.

Future Directions

One way in which increasing knowledge about contraceptive options such as Opill® can happen is to continue to push for a comprehensive sexual health education mandate in Oklahoma. According to the World Health Organization’s international technical guidance on sexuality education, part of a comprehensive sex education would include discussing the different types of contraceptive methods and how to use them. This detailed report lists access to modern contraception as a key sexual and reproductive health issue among young people, with studies finding that sex education curricula that include content about contraceptive use, as opposed to curricula that promote abstinence-only, are much more effective in “delaying sexual initiation, reducing the frequency of sex or reducing the number of sexual partners.” Additionally, comprehensive sexual health education is linked to increased rates of contraceptive use.32Aneesha Cheedalla et. al., “Sex education and contraceptive use of adolescent and young adult females in the United States: an analysis of the National Survey of Family Growth 2011–2017,” ScienceDirect 2, no. 100048 (2020). Therefore, it is likely that if Oklahomans were introduced to the wide variety of contraceptive options in their schools with trusted educators, the introduction of Opill® would have most likely made a much larger impact on populations across the state.

Another way Oklahoma can make Opill® accessible33Blair G. Darney, et al., “Evaluation of Medicaid Expansion Under the Affordable Care Act and Contraceptive Care in US Community Health Centers,” JAMA Network Open 3 no. 6 (2020). is by joining California, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Washington in state Medicaid coverage of over-the-counter contraception without a prescription.34Kaiser Family Foundation, “State Medicaid Coverage of OTC Contraception Without a Prescription,” 2024. North Carolina has also announced that Opill® will be covered without a prescription for Medicaid enrollees effective August 1st, 2024.35NC Medicaid Division of Health Benefits, “Opill to be Covered Without a Prescription,” NC Medicaid, July 17, 2024. By expanding coverage, Oklahoma women can be helped, including the 217,000 who live in contraceptive deserts36Power to Decide, “Contraceptive Access in Oklahoma,” November 2022. and the scores of Oklahoma minors who have lost Title X federal funding access for confidential birth control planning.37Ari Fife, “Without federal funding, Oklahoma minors lost access to confidential birth control and other family planning services at county clinics,” The Frontier, October 25, 2023.

According to these survey results, Tulsans need to be further educated about Opill®, and Tulsa clinicians are widely supportive of this option, especially given what it means for increased access. As Oklahoma continues its descent into a post-Roe era, ensuring access to Opill®, along with comprehensive education and supportive policies, is essential. It is only then that women can be empowered to take control of their reproductive health, giving them the opportunity and autonomy to confidently lead healthy lives.

About the authors

Kayla Cao*

Student at Duke University

Kayla Cao is a junior at Duke University majoring in Biology, minoring in Music, and obtaining a certificate in Health Policy. She is originally from Tulsa, Oklahoma, and had the privilege to work with Take Control Initiative as their Clinical Services Intern during the summer of 2024.

Candice Holley

Clinical Training & Data Manager, Take Control Initiative

Candice manages Clinical Training and Data for the TCI+ Quality Improvement Project at Take Control Initiative. She holds a degree in Health Education and Community Health and has worked extensively in clinical informatics and data integration. She has supported hospital systems and clinics across the United States, and for the last six years in Oklahoma. Her work is rooted in a commitment to expanding access to healthcare and advancing community well-being. She values the power of human connection, building trust, and supporting sustainable and meaningful change.

*corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Patient Survey Questions, English Translation

Appendix B: Patient Survey Questions, Spanish Translation

Appendix C: Patient Survey Flyers

Appendix D: Graphical Breakdown of Responses to Patient Survey

Appendix E: Clinician Survey Questions

Appendix F: Graphical Breakdown of Responses to Clinician Survey

Bibliography

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Gynecologic Practice. “Over-the-Counter Access to Hormonal Contraception.” ACOG, October 2019. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2019/10/over-the-counter-access-to-hormonal-contraception.

Brandwein, Sharon. “The Top Reasons Patients No-Show or Cancel.” Tebra, 2023. https://www.tebra.com/theintake/practice-operations/patient-scheduling-retention/the-top-reasons-patients-no-show-or-cancel.

Cheedalla, Aneesha, Caroline Moreau, and Anne E. Burke. “Sex Education and Contraceptive Use of Adolescent and Young Adult Females in the United States: An Analysis of the National Survey of Family Growth 2011–2017.” ScienceDirect 2, no. 100048 (November 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conx.2020.100048.

Daniels, Kimberly, and Joyce C. Abma. “Current Contraceptive Status Among Women Aged 15–49: United States, 2017–2019.” National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief, no. 388 (October 2020). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db388.htm.

Daniels, Kimberly, and William D. Mosher. “Contraceptive Methods Women Have Ever Used: United States, 1982-2010.” National Health Statistics Reports 62 (February 2013): 1-15.

Darney, Blair G., R. Lorie Jacob, Megan Hoopes, et al. “Evaluation of Medicaid Expansion Under the Affordable Care Act and Contraceptive Care in US Community Health Centers.” JAMA Network Open 3, no. 6 (June 2020). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6874.

Dehlendorf, Christine, Maria Isabel Rodriguez, Kira Levy, Sonya Borrero, and Jody Steinauer. “Disparities in Family Planning.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 202, no. 3 (March 2010): 214-220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.08.022.

Dennis, Amanda, and Daniel Grossman. “Barriers to Contraception and Interest in Over-the-Counter Access Among Low-Income Women: A Qualitative Study.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 44, no. 2 (March 2012): 84-91. https://doi.org/10.1363/4408412.

Fife, Ari. “Without Federal Funding, Oklahoma Minors Lost Access to Confidential Birth Control and Other Family Planning Services at County Clinics.” The Frontier, 2023. https://www.readfrontier.org/stories/without-federal-funding-oklahoma-minors-lost-access-to-confidential-birth-control-and-other-family-planning-services-at-county-clinics/.

Frederiksen, Brittni, Usha Ranji, Michelle Long, Karen Diep, and Alina Salganicoff. “Contraception in the United States: A Closer Look at Experiences, Preferences, and Coverage.” KFF, 2022. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/report/contraception-in-the-united-states-a-closer-look-at-experiences-preferences-and-coverage/.

Fuentes, Liza, Ayana Douglas-Hall, Christina E. Geddes, and Megan L. Kavanaugh. “Primary and Reproductive Healthcare Access and Use Among Reproductive Aged Women and Female Family Planning Patients in 3 States.” PLOS ONE 18, no. 5 (May 2023). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285825.

Gupta, Alisha H. “Women React to News About an Over-the-Counter Birth Control Pill.” The New York Times, July 14, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/14/well/live/opill-birth-control-over-the-counter.html.

Guttmacher Institute. “Interactive Map: US Abortion Policies and Access After Roe.” Guttmacher Institute, 2024. https://states.guttmacher.org/policies/oklahoma/abortion-policies.

Hartman, Melissa. “Opill: The First Over-the-Counter Daily Oral Contraceptive.” Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2023. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2023/opill-the-first-over-the-counter-daily-oral-contraceptive.

Hayes, Jana, and Alexia Aston. “Oklahoma Bill Would Shift Sex Education to Opt-In, Limit Teaching HIV/AIDS or Contraception.” The Oklahoman, February 21, 2024. https://www.oklahoman.com/story/news/2024/02/21/oklahoma-sex-ed-bill-proposed-danny-williams-opt-in-limits-contraception/72672955007/#.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Unintended Pregnancy. The Best Intentions: Unintended Pregnancy and the Well-Being of Children and Families. National Academies Press (US), 1995.

Kaiser Family Foundation. “State Medicaid Coverage of OTC Contraception Without a Prescription.” Kaiser Family Foundation, 2023. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/state-medicaid-coverage-of-otc-contraception-without-a-prescription/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D.

Kharraz, Oliver. “Doctor Appointment Wait Times Are Getting Worse.” STAT News, May 2, 2023. https://www.statnews.com/2023/05/02/doctor-appointment-wait-times-solutions/.

Krewson, Celeste. “Survey Finds Interest in Progestin-Only Pills Among Transgender Populations.” Contemporary OB/GYN, 2024. https://www.contemporaryobgyn.net/view/survey-finds-interest-in-progestin-only-pills-among-transgender-populations.

Lupkin, Sydney. “First Over-the-Counter Birth Control Pill Now for Sale Online.” NPR, March 4, 2024. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2024/03/04/1235404522/opill-over-counter-birth-control-pill-contraceptive-shop.

McDonald-Mosley, Raegan. “Facts.” Power to Decide, 2024. https://powertodecide.org/facts.

McKenna, Maryn. “States With Abortion Bans Are Losing a Generation of Ob-Gyns.” WIRED, 2023. https://www.wired.com/story/states-with-abortion-bans-are-losing-a-generation-of-ob-gyns/.

North Carolina Medicaid Division of Health Benefits. “Opill to Be Covered Without a Prescription.” 2024. https://medicaid.ncdhhs.gov/blog/2024/07/17/opill-be-covered-without-prescription.

“Roe v. Wade.” Oyez. Accessed November 18, 2024. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1971/70-18.

Share this page:

More from Metrilineal

Bleeding Behind Bars: Access (and lack thereof) to Menstrual Products in Prisons

Bleeding Behind Bars Access (and lack thereof) to Menstrual Products in Prisons Read More

Scolded at the vasectomy pre-op: Family planning is a heavily gendered responsibility, and that doesn’t make sense

Scolded at the vasectomy pre-op Family planning is a heavily gendered responsibility, Read More

Government Mandated Parental Leave in Oklahoma: Addressing Structural Racism

Government Mandated Parental Leave in Oklahoma Addressing Structural Racism Abstract In 2023, Read More